The Building Blocks of Musical Story

Reading Notes

22 Minute Read | Tablet or Laptop Recommended

Topics and Themes

Creative process in storytelling, Themes and motifs, Film score unity, Junior high school embarassment, Three types of musical motifs, Getting a unified score from your composer

My Most Embarrassing Story From Junior High School

I grew up in a time before smart phones, two day shipping, or free instructional videos a click away. Finding answers back then wasn’t as simple as getting your phone out; You actually had to walk up to a book stack and find a book made of paper. All knowledge came with weight. If you found a good book that suited your needs, you buried your nose in it. If not, tough cookies.

When I was in junior-high, just like practically all other junior-highers, all I wanted was to be cool and popular. Since there were no helpful after-school specials that offered specific steps on becoming popular, the only chance I had was to find a book on it. Surely, there was a book out there that had the answers that I desperately needed to survive and thrive in junior high school, right?

I had three options to find this book. I could...

Go to a bookstore. To make this happen I would have to convince someone to drive me there, find a book that could help me be more popular, and buy it without any judgement from the cashier. It’s almost like I could read their minds: “Why do you want that book? Are you really that desperate?” Nope! Couldn’t deal with that.

Go to the library. Considering how I desperately wanted to be cool, I never stepped one foot in any library because no one in their right mind would be caught dead walking around a library. Yeah, I was seriously enlightened as a 6th grader.

Order a book through a special catalog delivered every month to our homeroom teachers. I chose this option. It seemed private enough.

When the book catalog was passed out in the classroom, a brightly colored and thin sheaf that wouldn’t last a minute in the lightest rain, I thumbed through its 6 pages. I immediately found a book entitled How To Be Cool And Funny.

I thought to myself, “Yes! This is it! This is the answer to all my problems! I’m gonna be so popular after I get this book! All the girls are gonna want to go out with me! I’m gonna be king! I will rule junior high, forever!” I cobbled up my allowance and ordered a copy of this most important book.

Four weeks later, a big package of books was delivered to my homeroom class. I was really excited! I will finally learn the secrets to being popular, cool, and possibly even funny!

My 6th grade homeroom teacher, Mr. Coleman, was a teacher close to retirement by the time I had him. So, when Mr. Coleman called up each student to pick up their book order, he also decided to announce their book choice to the entire class.

Uh-oh.

What made it worse was that the shipping invoice was in alphabetical order... My last name starts with the letter W.

The three minutes I had to wait for Mr. Coleman to get to my name was unbearable. I wanted to jump out the window and escape on foot, hop a train, hit South America, live without Cheerios or Micro Machines or Gi Joe, get adopted by a pack of wild dogs, walk on all fours and eat like a wild animal, forget writing cursive, lose the smell of freshly Xeroxed copypaper, and let go of speaking a human language.

After what seemed like an eternity, Mr. Coleman finally announced: “Dave Wirth: Please come to the front of the class and pick up your copy of How To Be Cool And Funny.” Goddammit.

With everyone in the class staring at me, I dragged my heels to the front of the classroom. I picked up my book, forced my barely working feet to carry me back to my desk, and promptly buried my head in my arms. Even the motivational posters in the room were laughing at me.

Later that night, I burned the book in my backyard.

Part I: The Creative Process in Storytelling, Start To Finish.

Have you ever marveled at how stories get written at all? I mean, it’s an incredible thing, right? Stories start from nothing and end up becoming something.

When you look close at the creative process across different mediums of expression, there are some notable similarities. From charcoal sketches to graffiti, from simple guitar chords to massive orchestrations, from a spark of an idea into a beautifully fleshed out script, all creative ideas start from the same place: Nothing.

Sooner or later, we creators get the sense that there’s something just over the horizon of consciousness. An idea is waiting there for us to discover. It’s on the tip of our tongues. We wait for it, we search for it, and then we find it! It’s the idea that makes us think, “Ooooo, what is at the end of that?” It sweetly kisses the air around us, singing to us from far off in the distance like a siren song. If we follow that song to it’s origin, we do it with gusto, anticipation, and enjoyment.

Professional creators know that the ego takes a back seat in a true act of creation. If they’re diligent and committed enough, the ideas they find end up building on each other. At the end of this process, they can look at what they created and be surprised to see that it’s a living piece of art.

Had I not been paying attention, I wouldn’t have remembered the story I shared in the beginning of this article at all. It came back to me about two months ago in a hushed panic. Although I intensely felt the hot shame of this memory 20 years or so later, I still loved remembering the details. Frankly, when I remembered it and got over the fact that it actually happened, I laughed as hard as the motivational posters did. And writing it came easily. I had no idea what I was going to do with it, but I didn’t care. I followed my curiosity and just went for it.

The best part of writing the story down was when I had the realization that the story no longer belonged to me. The story began to live a life of its own, independent of me. It had a form; It felt alive. I was reminded me of a quote from Paul Klee (paraphrased, and if I’ve got the author wrong than tell me in the comments):

You know you’re done if you look at what you created and it looks back at you.

If you’re a writer or director, have you ever truly appreciated the magnitude of the moment where you know the story is looking back at you? Where it feels magical? Where it is brimming and bursting with energy? Where it’s alive? Have you ever wondered how on earth you got there in the first place?

If you’re anything like me, you’d just as curious about how a creative idea becomes alive, how this process works, how it happens.

Without a doubt I’m going to dissect the process in this article, but I promise you that I’ll be careful. Creativity is a mysterious, fragile force. There is so much of a miracle when what we create becomes alive. It’s delicate. What I’m attempting to do in this post is like taking a grandfather clock apart and putting it back together. Risky, but necessary, because with clarity and more mastery over the creative process, we can all create better scripts, better film scores, and better stories.

On that note, I will have a full section where I’ll be getting into film scoring and some examples later in the post. I want to talk generally about the process we composers go through to make a badass film score for you so you know what to expect. After all, this article series is called Storytelling With Sound.

Each creative process starts somewhere, and that’s where I’ll begin today. It’s not a bad idea to understand the strange, weird, lovely place that contain the origins of all stories.

The Origins of Story

From what I gather, many people have a hangup when it comes to creating something new. It’s a simple difficulty: How to start creating? It can be a little terrifying, for sure.

Luckily, starting can feel the same for everyone. Not even the most famous, successful, and prolific artists are totally immune to the difficulties of starting the creative process. The process is entirely democratic and indifferent to money, success, fame, or any other modern trappings.

And yet, this starting space holds just as much magic and beauty for a beginner as it does a seasoned professional.

Each artist who sets out in this starting place and sticks with it eventually feels the subtle pang of excitement that tells them this one idea or that other idea is the right one. It can be scary, but the more a creator allows herself to pay the prices of entry into that nothingness, which I think is a land of ideas, the larger the spoil when she emerges.

This space, this beginning part of the creative process, is what I like to call The Liminal Space.

The Liminal Space

One of my favorite books by the author Salmon Rushdie is Haroun And The Sea Of Stories. Originally written for his son, the novel is set in a secret, magical world. The world is hidden from the “real” world, one of factories, billowing waves of smoke, and gridlocked transportation. The magical realm can be entered by accident or by invitation, and it is a little of both for two characters in the book.

In this magical realm, there is a main body of water that is called the sea of stories. Stories naturally bubble throughout the sea, free for anyone to pick up. However, and here’s the catch, characters can freely dip into the sea of stories for inspiration as long as they are in that magical world in the first place.

I love this setup! First, that there is a sea of stories. Second, the world where the sea of stories resides can only be entered by accident or invitation. It’s not a place that can be entered willy-nilly.

This magical world is similar to the liminal space, and it’s the very beginning of our journey into creating, no matter the medium.

There are thousands of authors who refer to the liminal space in their works. One of my favorites is from Michael Meade in his fantastic book Men And The Water Of Life, where he writes about an initiation by water, and how intense it can feel:

The Water of Life can only be found by breaking down, by wandering away, by being and feeling lost. The world of water dissolves and wears away established patterns and accomplishments. Initiations by water begin with an accumulation of losses and sorrows, an expansion of emptiness inside, the feeling that life has stopped flowing in a natural and healthy way.

Phillip Pullman often writes of the many possibilities he knows before he writes the first sentence in a story. To him, that first sentence is the most important because it can define a story and it’s direction. Before that sentence is written, there are unlimited possibilities, but afterwords there is clarity. He defines this starting point as Phase Space, from his book Daemon Voices, Page 134:

Phase Space is a term from dynamics. It’s the notational space which contains not just the actual consequences of the present moment, but all possible consequences.

The Liminal Space is like the phase space. It is a space of ideas and possibilities. It is really similar to Haroun and the Sea of Stories in that there is a sea of stories freely available to those in the world. If you’re a writer/director, I imagine that you entered the liminal space when you created your stories, when you plucked them out of thin air. The same happens for me when I start a new score.

If this space is so awesome, why can’t we enter it all the time to get the best ideas? Well, to be frank, it’s the entering of the space that is troublesome. The liminal space doesn’t always welcome us into it. To enter the world of ideas we need to pay for admission.

Paying The Entrance Fees to the Liminal Space

As it stands, the liminal space is not a place many people enter willingly, and for good reason. It's a place where change is born. And for change to occur, there has to be a force or a feeling, something to push us forward into the confusing area of not knowing anything. Frankly, most of us don’t want to feel uncomfortable in quite this way, and to be clear: We will sometimes feel incredibly uncomfortable in the liminal space!

It’s not uncommon to feel a bit of depression, confusion, the upside-down-ness of this strange creative space. It’s like the carpet is being yanked out from beneith us. Yet, we need to be willing to accept being stuck, unsure, confused, annoyed, angry, and/or depressed in order to get that one idea that really makes sense. We make a sacrifice of our comfort to come out on top later. We must be okay with feeling a bit of indecision, fear, perhaps even outward aggravation that something is there but we just can’t find it… yet.

Why? Why on earth do we have to feel this way? Isn’t there someway around this sacrifice? Isn’t there another way? No, not really. To understand why, we have to talk about ego, just a little bit.

So, what does ego have to do with the creative process? Well, everything…

Role Of Ego In The Creative Process

I am willing to bet that the most experienced and successful creators in the world probably have a good relationship with their own ego. They must keep it in check during the creative process, or else it might streak throughout the creative playing field and piss on first base while it’s at it.

This three lettered word, the EGO, is somehow worried with creating something “good.” Judgements are the ego’s wheelhouse; Ego is very comfortable with labeling good and bad. And when a professional creator is in the act of creating, nothing can stop an idea dead in it’s tracks faster than the ego saying, “Whoa dude, that’s total shit.”

To enter the creative liminal space where the best ideas come to us, we must check the ego at the door and say, “Sorry pal, this is a private club.” As Julia Cameron advises us, we have to learn to let quality go and just focus on quantity. We have to relinquish all control and jump head first into the deep weirdness of not knowing anything. That is the price of admission: Not knowing if what you’ll create is gonna be considered “good” or “bad,” but engaging nonetheless.

Uhg. Is it worth it?

Without a doubt, yes.

Without entering the liminal space, the work I do as a composer falls flat. I have enough experience to recognize when I’m creating something that doesn’t have a spark to it, doesn’t interest me. It’s like I’m trudging through wet concrete. Yuck.

In my work, I constantly approach being as comfortable as I can be inside the liminal space. I enter it as willingly and effortlessly as I can. I pay the entrance fees with joy and gratitude. I check my ego at the door, and I wait for ideas to come to me. The trick is to be comfortable with creating anything at all from that space, to just try. If nothing comes, no biggie. Try again tomorrow.

But sooner or later, something starts to happen. Some strange momentum is starting to build, ever so subtly. And then, some small idea comes and whispers in my ear, “Hey, I’m an excellent friend. Let’s hang out!”

What a moment this is! I love it when the right idea comes to me. And it should come as no surprise that this is the next part of the process.

The Rumblings of a Distant Thunderstorm

When we enter the liminal space pay our entrance fee in full, its inevitable that we will start to feel it when ideas are in the air. As Neil Gaiman put it in his wonderful book Art Matters:

Stories are waiting like distant thunderstorms, grumbling and flickering on the grey horizon.

When we begin to feel a distant thunderstorm of ideas coming to us, they are a signpost. Something is a coming!

This distant rumbling of ideas is also like the siren song in the Odyssey, but the only death we get is the death of the ego. We creators are helplessly pulled closer to the siren song of a creative idea, and it is one of the biggest rushes we feel. And yet, we can’t feel that rush without surrendering our ego a little bit. We must let go! Unlike Odysseus, we are not tethered to a mast of a ship, and we won’t be lured to our doom if we follow that sweet song. Maybe our ego will temporarily feel death, but we come out unharmed and with a beautiful story.

And here’s the great news: This thunderstorm, this siren song that we follow, has the potential to clear away the effects of the liminal space. Like, if an idea pleases us, we’ll follow it and end up with an entirely new story, brimming with energy. And just like that, we have left the liminal space.

Oh, what a great feeling this is! We go from a deep confusion to having a clue about where we are going to go next! Ask any creative about this feeling, and they will tell you it’s intoxicating.

Before I move on, I have to write it again: We won’t be open to new ideas if we haven’t fully entered the liminal space in the first place. In my strong opinion, the liminal space offers an embarrassment of riches to creators who fully enter and submit to paying the entrance fees (aka confusion, frustration, or maybe just a blessedly benign indecision). When the ideas come, that’s when the momentum really builds.

Ideas Need Presentation

The distant thunderstorm, the sweet siren song, is just the beginning. It’s just the rumbling of an idea. It’s only in our heads. Sooner or later, doesn’t that idea need a physical representation in order to communicate to an audience?

If I never felt the pull to write down my mortifying junior high school story, it would still be knocking about down in the murky depths of my subconscious, like a ghost farting in the basement. Sooner or later, we have to begin to structure our ideas. In film composing if we don’t actually start structuring our music into something concrete and unified, let alone record them, we don’t have a chance in hell to serve the story or the audience because no one will hear it.

The physical representation of the creative matter, these solid building blocks of story, or creation, is tangible. It is the medium of which we present an idea to the audience. In film scoring, they are the building blocks of musical story. And these building blocks unify a story into a whole being, something that can be alive if it’s structured well enough.

The way that I see it, these unifying elements are called Elementary Particles. From Phillip Pullman, in his book Daemon Voices, I am truly indebted to him for coining the term.

So, what exactly are elementary particles, and how do they help film scores and stories live?

Elementary Particles: Building Materials of Story

Elementary particles are the basic building blocks of story, the vehicles for delivery that unite a story into a well-conceived whole. You could think of elementary particles as themes or motifs that are used to inform an audience of the real action and development of the story.

Let’s start with an example: Think of how many ways people fell and dropped in the movie Inception. Innocuous, right? I mean, how many times was this one simple action used, and in how many ways?

If you rewatch the movie, you’ll see a lot of this specific elementary particle being displayed in different ways, from being tipped over backwards into a bathtub full of water, to instructing others on how they will “wake up,” all the way to a spinning top not falling over. In my opinion, something as small as this action can help to frame a narrative, and many narratives weave multiple motifs and themes into a single story. It’s no different from film scoring, as I’ll show you later in this article. For now, keep an open mind that these actions can be important vehicles to a story. After all, without that elementary particle of falling, how else do these characters "wake up” in Inception?

I’m not a film theorist by any stretch, but it’s hard to deny how unified Inception feels due to many interlocking motifs that we see throughout the movie. So, could we refer to elementary particles as motifs?

Sure!

Elementary Particles as Motifs

There are unlimited ways to physically unite a story as a living form, but for simplicity’s sake, you could think of elementary particles as recurring motifs.

Elementary Particles can be as subtle as a distinct color palate (i.e. yellow in Enemy by Denis Villeneuve), as bombastic as a shark fin slowly disappearing beneath the surface of the water, like waking up from an induced dream by falling backwards, or something as innocuous as walking. Motifs are used in a way that informs the story, and most importantly gives a sense of continuity.

Let’s bring this back to my humiliating junior high school story. Look closely… Did you notice an elementary particle in my story? I purposely included one: Walking.

I used this motif to unify my story into a comprehensive whole. Further, I used it to show you how I was feeling without being explicit about it:

"You actually had to walk up to a book stack” - Expressing inconvenience.

"No one in their right mind would be caught dead walking around a library” - Shame, fear of embarrassment

“Be raised by a pack of wild dogs, walk on all fours and eat like a wild animal” - Imagination of Dave Wirth circa 6th grade

"I dragged my heels to the front of the classroom.” - Reluctance to feel embarrassment

"I picked up my book, forced my barely working feet to carry me back to my desk” - Overwhelm and overstimulation

This elementary particle helped me present and unify my story. If I did my job right, it does so in a subtle way. It’s my hope you didn’t notice it until I pointed it out. And, there are some other elementary particles hidden in my story, too.

Whatever you want to call them, however you want to use them, elementary particles or motifs or themes or whatever, they can structure and unify a story. They are flexible, they are ready to be employed to show things that aren’t explicitly mentioned in dialogue (just like a specific camera angle can show what a character’s motivations are). When used correctly, they can give a story a skeletal structure. And, when stories have that structure, they have a much higher chance of living on their own.

And now we approach the final aspect of creating: The moment when we realize we are done.

Towards Living Art

In review: Stories start when creators agree to pay the price to enter the liminal space. They allow themselves to feel disheveled, confused, and possibly depressed. Sooner or later, the electricity of an idea is felt over the horizon of the consciousness. They work with that idea, fashion it into something physical using elementary particles that they gravitate to (walking, in my story for instance).

From there, what happens?

The final stage of the process is a quick one. It’s literally just a realization. It happens when you're looking closely at a piece of art that you worked on, perhaps for years, and you recognize that it’s looking straight back at you. I imagine that this is how Christopher Nolan looks back on Inception or Steven Spielberg looks back on Schindler’s List. These stories live on their own, independent of their creators.

If you’ll remember my paraphrased quote from Paul Klee:

You know you’re done if you look at what you created and it looks back at you.

There it is. The creative piece of art. It is living, all on it’s own! We want to experience the moment of creating a living something. It feels so good to create something that really connects with an audience, serves them, gives them something they desperately need in their lives. The best stories in the world have this living quality!

So far we’ve been focused on the creative process with regards to storytelling with words. I showed you how I used the elementary particle of walking to inform my truly humiliating junior high school story.

Now it’s time to shift our focus onto sound and music. Does the film scoring process look any different? Does creating music have any similarities or differences creatively than other mediums?

Definitely. Knowing how the creative process works for a composer and what kinds of elementary particles he/she can use can only help you with your stories. Paying close attention to that will help you with grow your career, if that’s a concern to you.

So, let’s jump into understanding what to expect from your composer in their creative process and how they can create a unified narrative in sound like you did with word. In this section, I will talk extensively about options you have for musical elementary particles. Knowing that will give you an edge.

Part II: The Building Blocks of Musical Story in Film Scoring

As composers, our first moment sitting down and looking at a film is the liminal space for us. We may know exactly what you’re asking for, but we have to enter the space of not-knowing. We must experience the absolutely crazy feeling that we don’t have any clue what we are doing. Any composer who says they never get even a tiny bit doubtful when first starting a score is lying through their teeth!

Hans Zimmer hilariously described how he avoids the liminal space: He often asks his team of engineers and musicians to do crazy things that he “needs” before he starts messing around with the theme of the movie. When he does actually sit down to compose, he may even sit on his hands and not allow his piano skills to dictate what themes come to him. This is his liminal space. He wants to sit with the movie and find the world that the story lives in, and he’s trying to find the one musical elementary particle that he can depend upon throughout the movie he’s scoring.

It’s our jobs as film composers to show up, try things out, and to allow ourselves to feel the confusion and indecision. If we can muster the strength enough to tolerate that period of weirdness, we will end up getting something. The distant rumblings of ideas sooner or later come to us, and we gain confidence. Once we have your approval, we can build you a score that really fits your movie like a glove.

Speaking of building you a score, we composers have tons of ways to approach your project. Tons! Our job is to find what type of motifs, or elementary particles, are appropriate for your film and then deliver that score in a timely manner.

To get started, it’ll be helpful for you to know just a tiny bit about what kinds of building blocks, what kinds of elementary particles, are available to composers. I’ve included three elementary particles that I love working with.

To start, lets go with the most common elementary particle in film scores: Melody.

Musical Elementary Particle #1: Melodic Themes

When it comes to uniting a movie’s film score into an interweaving web of motifs, melody is definitely the most classic.

Melodies are basically a series of single notes. It’s really that simple. Then, if a particular series of notes are repeated, this melody could be known as a theme.

A very famous musical theme would be from the first movement of Beethoven's fifth symphony. Hector Berlioz penned another memorable theme in his Symphonie Fantastique. When we hear these themes, we quickly think of these pieces of music, not unlike when someone sings the Star Wars theme.

Melodic themes are incredibly flexible, just like the elementary particle of walking that I presented in my story. Composers can take a single melodic theme and use it in different circumstances, to describe different moods and motivations.

The most famous example of a film composer using melodic themes in film music is John Williams. He often creates themes for just about everything in a movie, including themes for the movie itself, specific characters, and even repeated actions. This isn’t a new idea (though the way John Williams does it is incredible). These are traditionally called Leitmotifs, and they could be thought of as smaller melodies that get repeated in specific points of a narrative. John Williams weaves a brilliant tapestry of melodies into his scores and creates a living, breathing piece of art that way.

Other film composers tend to be a bit more spare with the amount of melody present, but their scores are no less effective. The score for First Man by Justin Hurwitz is an example of a melodically themed score that is more spare and minimalistic than a typical John Williams score. He presents the melodic themes in different ways according to the action on the screen; A different orchestration here, a different mood there, a different action somewhere else. It's a brilliant soundtrack.

The best part of melodic themes is that there is just so much a composer can do with them. A single theme can provide enough material for an entire movie, including the underscoring, if you wanted it to. When a composer uses multiple themes, he exponentially increases the amount of variety of melody in a movie.

Melodic elementary particles have exactly the same function as do the elementary particles do with the written word: To give structure and to unite the story. Just like walking in my ridiculous story of humiliation, melodic themes can help to inform the audience of what's really going on, but in a subtle way.

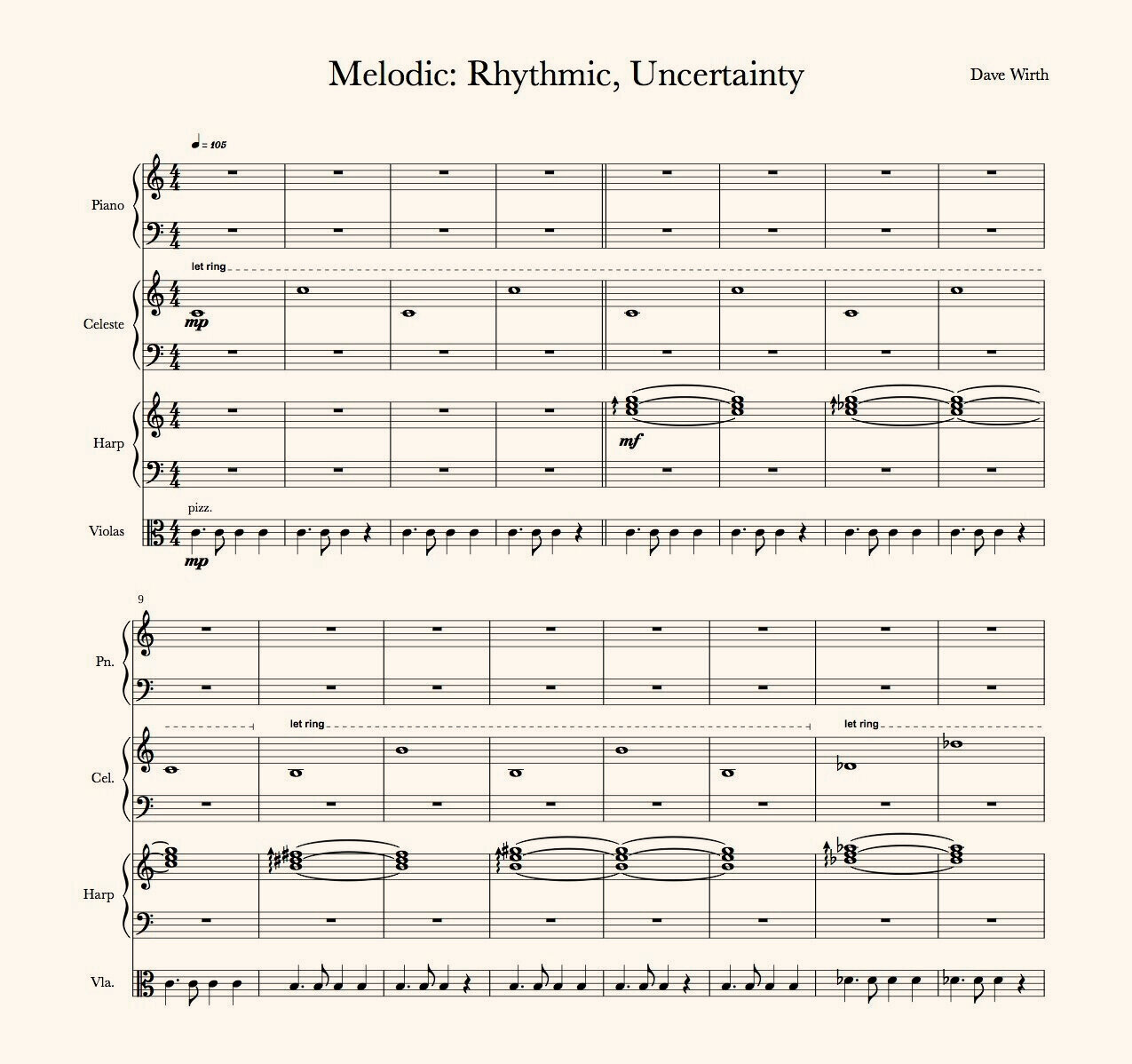

Let's jump into some examples. In each of these, I composed one main melodic theme which could represent what a viewer hears at the start of the movie. From there, I recycled parts of this main cue to make it appropriate for other related cues that needed different vibes. My aim was to create an interlocking web of melody that felt unified throughout five examples, like a miniature film score.

Let’s jump in! Here’s our main title sequence:

Composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

The first example established the framework for the “movie.” From this point forward, I am officially allowing myself to recycle parts of this example and reuse them in different ways.

So, to create that unified structure, I first took the melody from the piano in the main title and re-orchestrated it with the horn and oboe. Then I took some sound clusters from the melodies and the bass line and created the piano part. Here is the result:

Composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

Okay, now what can I recycle? Well, why can’t I use just the chords that the celli and the two french horns were playing, and use them for underscoring?

Composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

Now that you know that we have some flexibility with our material, what would happen if we wanted to create a cue that sounded disconcerting? Absolutely possible, but to get there we need to get even more subtle.

First, take a look at the timpani in the main theme. If you were paying close attention to it, you’ll see that it is playing a very distinct rhythm in measures 3-4. In this next example, why don’t we reuse that rhythm? Second, if you were paying really close attention to the viola in the main theme, you’d notice it was playing only one note. Why not take that rhythm and one note and combine them? It could be a bit tense!

This cue could describe a point in time where characters are unsure, but still engaged with looking for answers. The important point is that it’s still united in feel and presentation:

And finally, why can’t we make an incredibly gentle cue? The opposing melodies in the strings and the piano in the main theme sequence can be played in a totally different rhythm, and slower overall tempo. This would be ideal for the moment when we are going for something that is more intimate, a moment between two people, exchanging knowing looks with each other:

Composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

Flexibility in Melodically Themed Scores

Melodically themed film scores are classic, diverse, and incredibly flexible. They are a respectful nod to the golden age of cinema and can be appropriate for many styles of movies. They can be used to describe multiple moments in a film and unite it, either by using a single theme throughout or by using leitmotifs for every single action or character. Melodic themes can be used on a small-scale movie that’s set in one room, or they can be used on a film that’s set in multiple places in an unknown universe.

Melody is flexible.

But what if you want more subtlety, something a little less in-your-face, musically speaking? What if you dislike the idea of having a epically melodic score, like John Williams would write? What if you want something simpler? Easier? More relaxed? Slower moving? Subtle?

Musical Elementary Particle #2: Harmonic Themes

Sometimes in movies, you’ll hear music without there being a melody. In these movies, you could very well be hearing a harmonic theme. Harmonic themes are basically chord progressions: Two or more chords pressed together in linear time.

Chord progressions have an obvious advantage over melodies: They can easily stay out of the way of the action while still telling the story beyond the story.

Take the score for Moonlight by Nicholas Britell for example: A simple chord progression with a violin. It works brilliantly in this movie, perfectly appropriate for the pace. Another great chord progression that comes in a form of a theme is the opening chords for the Netflix series Sense 8. Those chords are the perfect start for this show. It’s memorable, it’s not hard to follow, and it described the show in less than 10 seconds.

Harmonic themes can be used to unite a movie in the same way that a melodic theme can. They can be used in different ways, orchestrated differently, and describe multiple moods. Also, they are fantastic for underscoring.

In this next main title sequence, I allowed myself only two instruments: A guitar and a piano. Let’s say that this was the first thing a viewer heard when they saw a movie:

Composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

Well, okay. We’ve got the chill and gentle and secret love vibe going. But what else can we do with it? Can I take what I’ve established and create a different vibe using only two instruments? Of course.

For this next example, I switched up the rhythmic duties to the guitar and make it sound more whimsical, but I kept the same chord progression.

Composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

Now if you are a musician and happened to play each of these parts on piano or guitar, you’d notice that I included a sneaky note that is always playing throughout all the chords, either by the piano or the guitar. It’s technically called a melodic pedal point, but you could think of it simply as a single note that is played throughout a progression, no matter what else is being played.

Why can’t I have the guitar play only that melodic pedal point, and have the piano play related chords in a similar chord progression? The result is that it feels a bit unstable and uncertain, perfect for a point of indecision in a film:

Composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

And finally, if we wanted to have a cue that was extremely gentle, we can use the guitar for something it’s uniquely qualified for: Fingerpicking. Fingerpicking has always had a gentle feeling associated with it. To achieve this, the guitar plays a simple fingerpicking pattern while the piano plays in a gentle way, lightly accenting the music. It’s even more intimate, cozy even, than the others:

Composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

Harmonic themes offer a different approach. If you prefer subtlety, if you don’t want the music to swiftly take the viewer on a big emotional journey, a harmonically themed score might be just the ticket. It works marvelously in movies where the pace is slower, the editing is slower, and the audience has time to absorb nuance.

But is that all there is? What if you don't want the grandiosity of a melodically themed score, nor the subtlety of a harmonically themed score? What if you want something more experiential, something more immersive, something that could be downright frightening in some aspects?

Enter textural themes.

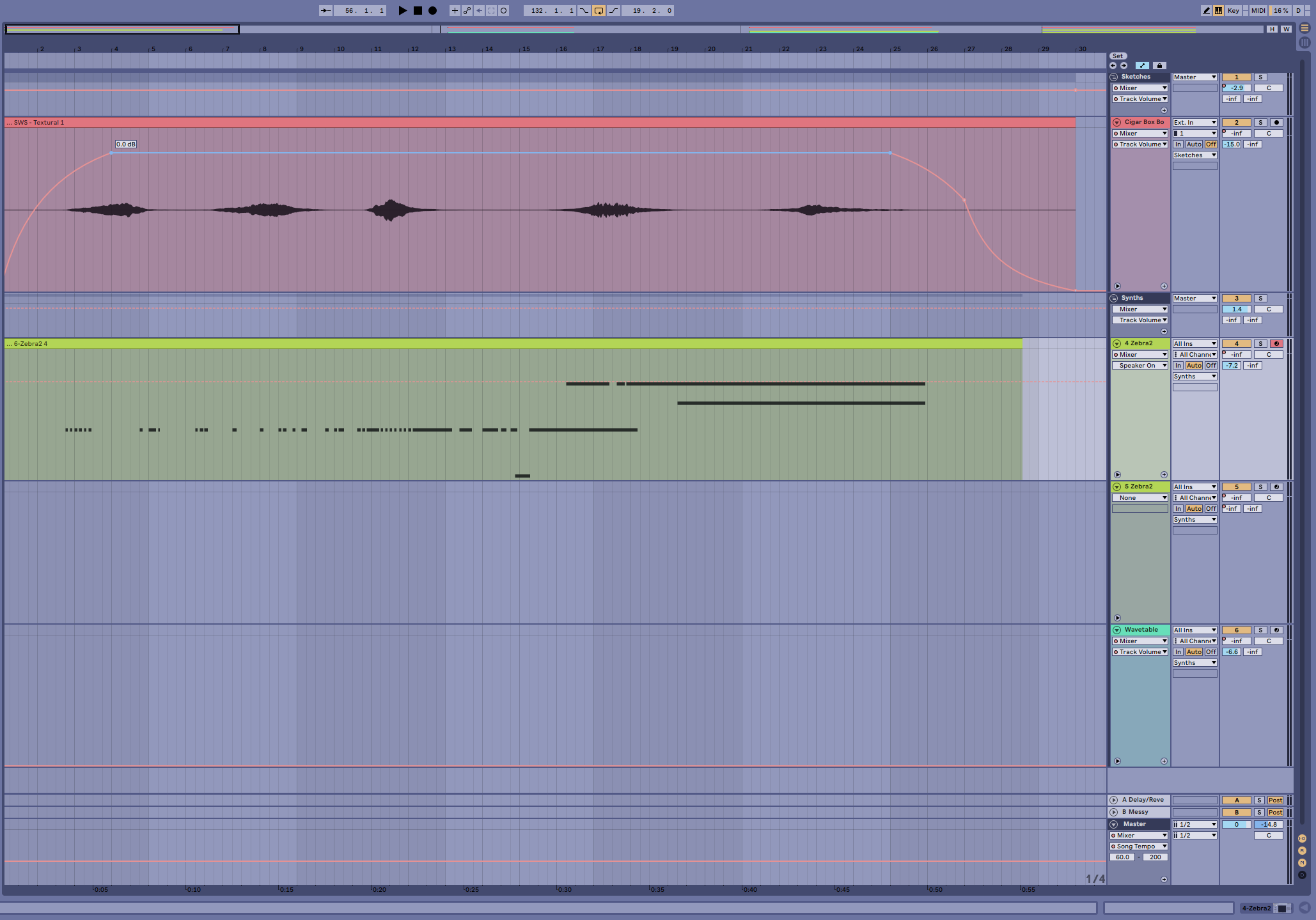

Musical Elementary Particle #3: Textural Themes

One of my favorite film composer teams is Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow, widely known for their synthesizer-based scores. Though they still make use of melodic and harmonic themes, I highly enjoy listening to their use of analog synths to create an ambient musical immersion into the world of the story they are composing for.

Take Ex Machina for example. Yes, there is a melodic theme in the movie, but at the same time there is a bounty of ambient electronics throughout. Another wonderful score from this composer team is Annihilation. The electronics they used perfectly captured the Shimmer, an expanding void that annihilates and changes everything in the story of the movie. It is a brilliant score. Whenever I listen to it, I am instantly transported inside the film.

Texture can be used to create a sense of space in a movie, one that can be immersive without being overwhelming, one that can bring the listener deeply into a state of being without telling them what to feel.

Cigar Box Noisemaker by AMBO Art

To achieve a unified sound, I decided to use a guitar that my good friend WT from AMBO Art created for me recently: A cigar box guitar that was meant to create strange sounds. I decided to use this instrument and a couple of digital synthesizers to create a landscape we could enter and feel like we were a part of. My intent was to create an immersion into a world that felt deathly and grim:

Since I established that this is a more textural theme, and since I established that sound of the bowed cigar box, why can’t I use it in a more apprehensive, almost combative way?

Similarly, I decided to make the next one be incredibly rhythmic, something weirdly galvanizing, something not totally of this world. It reminded me of a deathly march:

And then, we need our “story” to resolve, right? Well, that challenged me because well, how do I make something like this actually sound more gentle? Or at least as gentle as it can be made?

Here’s what happened:

And just like that, a unified textural theme.

Finding the Best Possible Musical Theme For A Film

Finally we have arrived to the real question: How do you decide what type of elementary particle, what kind of theme is best for your movie's score?

Let’s start with the fact that your movie is unique. It’s very possible that a mixture of each of these elementary particles, or even ones I didn’t present in this post, could be the best way forward. And maybe you, as the director, don’t even need to know this for certain. The only thing we’re all sure of is that the score must enhance the film. It must be appropriate for your movie and support the story.

The best part of working with a composer is that we can help you find and structure the musical representation of the story. We really care about music, and we want to make sure your movie is enhanced with our efforts.

For us composers to understand your movie truly, we have to feel it. We have to know it as well as you do. To be totally clear: We don’t often need you to be able to say exactly what orchestration or compositional technique or chord progression or melodic technique is needed, but what we do need is your view of the film and the story.

To get there, try to be open about what your movie is about, it's theme, it's essentials. Talk about everything with the story, the world the story lives in. Talk about the color, the cinematography, the acting, the editing, and the sound of the production. Talk about how it was filmed, where it was filmed, why it was filmed the way it was filmed, and what you were working to accomplish. The composer will pick up ideas naturally from this discussion. She will figure out an appropriate way forward if you’re willing to talk about your story and your expectations. In short, you’re priming the composer to understand your film before she goes about writing for it.

Once we composers have some clarity about the world you’ve created and the type of score you want, we have to willingly enter the liminal space for ideas. We pay the prices of confusion and indecision. And quite possibly, we might have a brilliant idea hit us that is perfect for the movie on the first try.

If it were me creating your score, the only ideas I would present to you would be the ones that I think would encapsulate and serve the film. For me, the theme must be special, possibly special enough to be remembered, but not so special that it overtakes the movie and the story you’re presenting.

And then, the collaboration continues. I always ask for the director’s feedback on any potential direction because it saves time and frustration on both sides. I’ll send some sketches. I’ll send some rendered videos of the elementary particle in action. I’ll send a quick sample that gives a faint idea of a possible direction. If a director doesn’t like it, then the conversation starts anew, this time with more clarity. I actually love it when I miss the mark because it means I have a clearer direction!

Again, I’ll enter the liminal space, I pay close attention to distant thunderstorms of ideas, I create some sketches. And eventually, I’ll find the right foundation for the score that the director loves. It’s a simple process of elimination.

Once the director and I are united as far as the direction, then comes the fun part: Scoring for the scenes. I’ll use the elementary particles that I’ve established that the director likes, and I’ll create the first scene. Then keep going.

My aim at this point is to build on the ideas with the chosen elementary particles until the score helps the movie become a living beast. I want that movie to become something that looks back at the audience.

The Building Blocks and Elementary Particles of Story

There are trillions of ways of creating a solid, unified score, and they are as varied as the amount of composers actively composing.

You may already have a script that is totally banging… just brimming with that creative energy. Taking time to work with a composer on the most appropriate film score could bring your movie to the toppermost of the poppermost, to quote John Lennon.

Finding the exact right kind of score, one with the correct audio perspective, orchestration, or any sort of elementary particle, can be tough. I’m not afraid to enter the liminal space to get there because I know the embarrassment of riches, the spoils of that in-between space.

Sooner or later, the right elementary particle comes along that can help unify a story completely.

Just like walking was the elementary particle that allowed you to feel how I felt as a junior high schooler desperate to be popular without spelling it out for you, unifying a movie through multiple motifs can create a wonderful experience for a theater-goer. An appropriate soundtrack can aid you in your quest to create a movie that looks back at you when you’re finished.

And lemme tell you: The audience loves a beast.

Please, leave me a comment!

Or, feel free to reach out to me.

More Articles on Film and Music

Copyright Notices

All music that appears on this article was composed by Dave Wirth, Copyright and Published 2019 Fire, Fire, Red Star Down! ASCAP. All Rights Reserved.

Public performance of the music without written permission is strictly prohibited.

The music on your film is a powerful tool to deliver fresh perspectives, and believe me: Fresh perspectives are vital. This article goes deep into Audio Perspective, i.e. the music being written from the most compelling perspective in the story. Mastering audio perspective can make your movies far more relevant, relatable, and successful.

If you’ve ever wondered how you can use music to communicate a compelling perspective, this article is for you. Let’s hit it!